Cairngorms Connect Volunteer Gareth has been hunting for beetle treasure in the deadwood of the Caledonian pine forest. In this blog, he explains what these beetles can tell us.

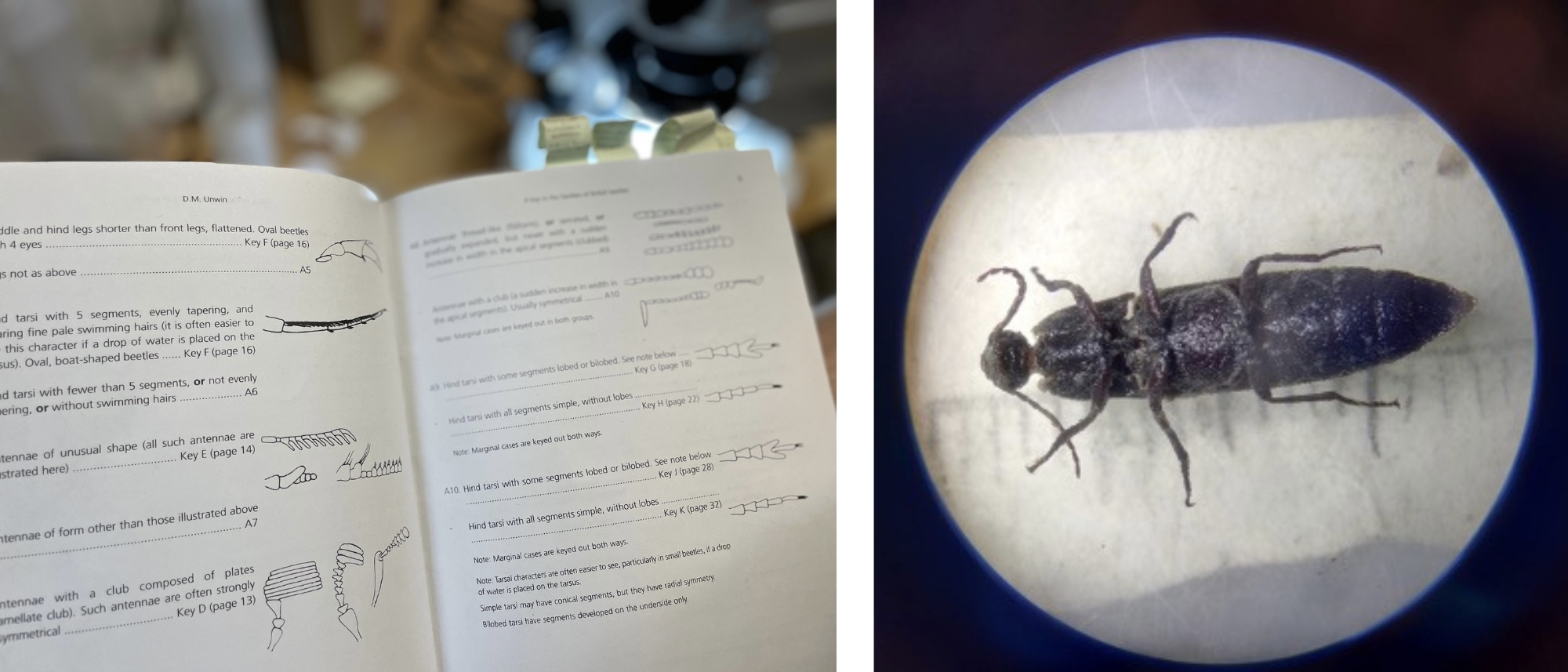

One, two, three … four? I check the key, leafing through the pages until I find the section for antennae not clubbed, tarsi (leg segments) simple. Were they simple? One of them did look suspiciously lobey…

Conviction may be the most difficult thing to master when ID’ing a beetle under a microscope. I have been ID’ing beetles for a month now and I still tremble at the sight of a beetle with features I haven’t had the pleasure of seeing before. Each new sample opened has all the possibilities and joy of finding a treasure chest buried on a distant island by a paranoid pirate. The treasure: shiny exoskeletons reminiscent of the brightest jewels, intricate woven tapestries on the back of chequered beetles, and the myriad of magnificent forms and body shapes. Except this treasure is not found in a typical treasure chest, nor for that matter from a typical “treasure” island. This treasure can be found hiding within the fallen branches and trunks of trees found much closer to home. This treasure is from the Caledonian pine forests, islands in their own right. Islands which are at risk of disappearing.

Identifying beetle samples. Credit: Lizzie Brotherston. Beetle sample through the microscope. Credit: Gareth Powell.

So why am I sitting here ID’ing beetles? What has that got to do with the plight of the Caledonian pine forest? The beetles help us answer an important question. Through their quantity and diversity, they can inform us about the health of these forests. Especially one particular habitat: deadwood. You have probably heard that trees are worlds of their own, supporting a vast array of different species in life. This is true, and continues when the tree dies. Potentially, over 20% of Caledonian pine forest species will use deadwood at some point in their lifecycle[1]. One of these species groups is beetles.

Deadwood is the perfect hotel of the beetle world; free accommodation and an all you can eat buffet. Would you like a room with view? How about this beautifully crooked snag? Or something closer to the ground? This stump has been nicely degrading for the last few years! Deadwood is crucial to most of the forest’s inhabitants, not just the beetles, but unfortunately, it’s not there in the volume it should be. After years of plantation forestry and a general obsession with instilling nature with the neat and tidy habits of our homes, the volume of deadwood sits on average around 10 times less than the natural value expected in our native woodlands(2).

Deadwood creation. Credit: scotlandbigpicture.com

This is where Cairngorms Connect comes in. Deadwood creation is a simple idea, but it is important to execute it right. Restructuring is the method used in sites previously used for forestry, selectively thinning the trees through ring barking, winching, and felling. This creates a mixture of standing and lying deadwood in amongst the once uniform trees – the perfect real estate for some beetles to move in. For this reason, the beetles provide a useful method of monitoring the effectiveness of this treatment when compared to untreated sites and seminatural woodland. The greater the diversity and quantity of beetles, the healthier the forest. To find this out, we need to trap the beetles. So our dedicated team set off across the Partnership setting up vane traps. Vane traps are a pretty simple contraption. Dangling from a tree, a wee bottle is filled with methylated spirits which lures in invertebrates attracted by the smell, two crossing plastic panels then intercept them in flight. Now, unfortunately they don’t survive the interaction with the spirits but every month, the team goes out to collect the bottles and see what’s flown in. Then it’s lab time!

Vane trap as part of the deadwood creation trial. Credit: Christina Hunt

ID’ing beetles should allow us to understand the impact of the work we are doing. Providing I manage to finally key out this beetle mocking me from the petri dish. Ahh, fantastic! Sometimes it’s best to take a closer look at the underside of the beetle. Now blatantly obvious, protruding from between the front legs was a nice little sticky out bit (a very technical term). I’ve met this family before! Elateridae! A click beetle, so named for the ability to spring out of danger while making a satisfying click noise. I write in the data, then plop the individual into the bottle with the rest of identified samples.

Looking outside, the pines rustling in the wind are no longer visible in the dark that’s crept over the forest, and I realise it may be time to head off home. I flick off the lights on the microscope and place the lid on the sample bottle. As I make my way out the door, I glance at the remaining samples to be identified. Looks like there’s a few more months left for me and the beetles yet. More deadwood treasure chests to be opened from the Caledonian pine forest!

This work is supported by the Scottish Government’s Nature Restoration Fund, managed by NatureScot.

Further Reading

1. Siitonen, J., 2001. Forest Management, Coarse Woody Debris and Saproxylic Organisms: Fennoscandian Boreal Forests as an Example. Ecological Bulletins, 49, 11–41. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20113262

2. Cathrine, C. & Amphlett, A. 2011. Deadwood: Importance and Management. In Practice 73: 11-15.

3. Martikainen, P., Siitonen, J., Punttila, P., Kaila, L., Rauh, J., 2000. Species richness of Coleoptera in mature managed and old-growth boreal forests in southern Finland, Biol. Conserv. 94, 199–209. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0006-32

Rosie Beetschen joins a day of Seed Establishment Trials in the beautiful and remote Strath Nethy to learn about how Cairngorms Connect are working to grow and expand our native forests. Listen or read.

Rosie Beetschen reflects on the Cairngorms Connect Community Conference earlier this month, and an amazing year of projects, fieldwork and volunteering